What to do when your child shares “bad thoughts”

When your child shares “bad” or intrusive thoughts, your response matters. Learn how to support them with empathy, identify when to seek therapy, and teach healthy coping tools to ease their mind.

Few things are more heart-wrenching for a parent than watching their child struggle with intrusive (bad) thoughts. Most parents want nothing more than to take away “bad thoughts.” While your first thought might be to reassure your child that these thoughts don’t mean anything, there’s something more powerful you can do: teach your child how to respond to these thoughts.

Key Takeaways

- “Bad” or intrusive thoughts are common in kids. They can occur for a variety of reasons, including stress and mental health conditions.

- The way you respond to your child when they disclose these thoughts is important. Listen without judgment and reassure them.

- If the thoughts are significantly interfering with your child’s everyday life, it’s time to get help from a therapist.

Why a child might share troubling or “bad” thoughts

Most people (including kids) have troubling thoughts from time to time. Research indicates that greater than 70 percent of children have reported intrusive thoughts. Children might call these “bad thoughts.” These thoughts are intrusive and can range from disturbing thoughts about harming someone to distorted thoughts about one’s body image. Children may experience “bad thoughts” for a number of reasons, including:

- Stress

- Mental health conditions

- Trauma

Sometimes, intrusive thoughts are a normal part of development, especially during the pre-teen and teen years. However, if a child or teen obsesses over these thoughts too much, it can significantly interrupt their day-to-day life.

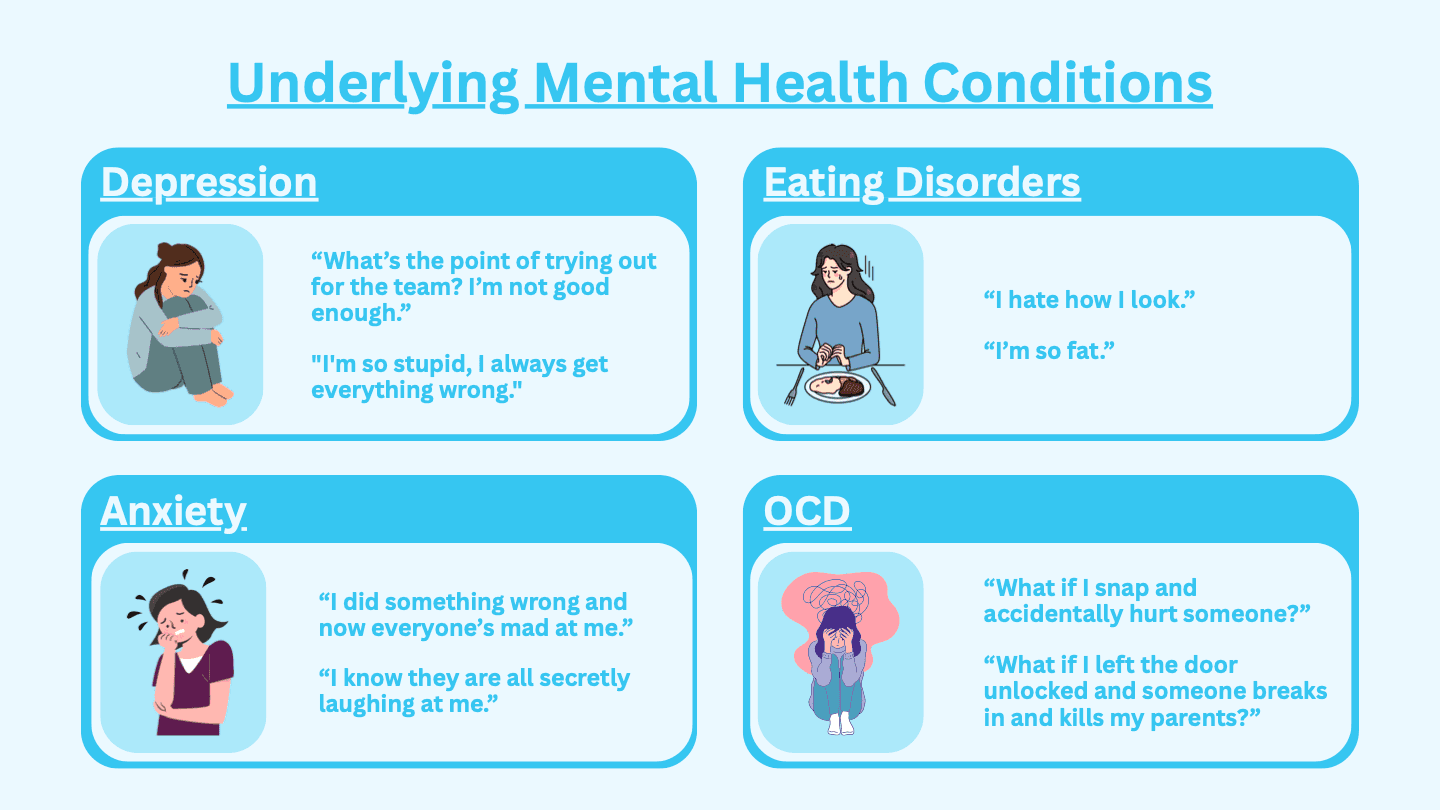

Underlying mental health conditions

Many mental health conditions may cause intrusive or “bad” thoughts, including:

- Depression - Depression may cause negative thoughts such as “What’s the point of trying out for the team? I’m not good enough,” or "I'm so stupid, I always get everything wrong."

- Anxiety - A child with intrusive, anxiety-related thoughts might have thoughts similar to these: “I did something wrong and now everyone’s mad at me,” and “I know they are all secretly laughing at me.”

- Eating disorders - Negative or distorted thoughts are quite common in eating disorders. Common thoughts include “I’m so fat” and “I hate how I look.”

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) - Intrusive thoughts are a core symptom of OCD in children. An example is “What if I snap and accidentally hurt someone?” Another example is “What if I left the door unlocked and someone breaks in and kills my parents?”

The difference between attention-seeking and a cry for help

A cry for help reflects a struggle to cope with overwhelming thoughts or emotions. Sometimes this cry for help comes in the form of attention-seeking behavior. Children may engage in attention-seeking behaviors to get help.

How to respond when your child confesses difficult thoughts

When your child comes to you feeling sad, anxious, or uncomfortable about their “bad” or intrusive thoughts, it can be overwhelming for both you and your child. But how you respond in the moment matters a lot. What they need is a judgment-free zone where they know they’re safe, no matter what their brain says.

Stay calm and listen without judgment

When your child discloses “bad’ or disturbing thoughts, take a deep breath and respond with a steady, calm voice. This will help them feel less anxious even in the middle of talking about something scary. When they are finished talking, thank your child for opening up. You can say something like: “I’m really proud of you for saying that out loud. I know it must have been scary.”

Ask gentle, open-ended questions

Ask questions to try to better understand these thoughts and how they are affecting your child. You might say something like: “Does something make that thought pop up or does it come out of nowhere?” and “How do you feel when you have that thought?”

Reassure them they’re not “bad” or in trouble

Let your child know that everyone has upsetting, unwanted thoughts from time to time — even grown-ups. Reassure them that this doesn’t mean that the thoughts are true.

Teach coping mechanisms to handle future “bad thoughts”

You can help your child think differently about upsetting, intrusive thoughts so they don't feel controlled by these thoughts. Let your child know that these are just thoughts and they don’t have to act on them. Teach them how to ignore the thoughts. You can try saying something like this: “Our brain is like a radio, sometimes it plays things we don’t like. We don’t have to listen if this happens.”

What not to do when your child opens up

Don’t interrogate them. Let your child do the talking. Don’t shame them for the thoughts. This can discourage them from sharing in the future. Also, don’t dismiss their emotions or minimize their feelings. Avoid phrases like “your just saying this for attention."

When to seek professional support

When the intrusive thoughts are very overwhelming for your child or they interfere with your child’s sleep, school, or social life — that’s a sign it’s time to get help. Getting help is especially important if your child seems anxious or depressed about the thoughts.

You and your child do not have to face this alone. Mental health professionals understand and know how to help.

Personalize intake session with a licensed clinician

Explore therapy, medication, or other options and determine the best next step through a personalized clinical session.

Signs your child might benefit from talking to a therapist

Here are a few signs it might be time to bring in a therapist — someone who can help your child carry what feels too heavy alone:

- They have a short fuse — they are frustrated or irritable and often snap at others.

- Worry is running the show — it’s a constant in their life.

- They no longer find happiness in the things they used to enjoy.

- Sleep and food are out of balance — too little, too much, or changing in other ways.

- They seem stuck in sadness, or talk about not wanting to be here.

These signs are your child’s way of saying, “I need help.” Listening to them is a powerful way to help your child heal.

How to explain therapy to a child in a supportive way

It’s normal for children (and adults!) to feel nervous when starting theapy for the first time. Before the first therapy session, talk to your child. Help them understand what therapy is about. Let them know what to expect.

Explain that they are not going to therapy because they are in trouble. It’s also not something to be ashamed of. Let them know that therapy is a safe space to talk about the intrusive thoughts that they have been having. Explain that a therapist can help them get rid of these thoughts.

If you’ve personally been to therapy, this is a great time to talk about your experience (in a positive, kid-friendly way). You can say something like: “I’ve been to therapy and it really helped me feel better. I think it can help you too.”

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the “bad” thoughts that your child is dealing with doesn’t have to control their life — or yours. Yes, they are hard to deal with, but with the right strategies and support, your child can change or even get rid of these thoughts. Therapy is a game-changer for helping your child cope with “bad” or intrusive thoughts. You can help, as well, by encouraging your child to open up and providing them with non-judgmental support.

Empowering your child to overcome intrusive thoughts

If your child’s “bad” (intrusive) thoughts are taking over their everyday life, it’s time to get them the help they need. At Emora Health, we believe every child deserves a safe and judgment-free space to talk about their thoughts, find peace, and develop the tools needed to cope with these thoughts.

Our therapists can help your child navigate those tough moments with proven therapeutic strategies. You don’t have to go through this alone. Reach out today and let us help your child feel happier and more in control.