Trauma-focused CBT vs CBT: What Parents and Teens Need to Know

Explore the key differences between Trauma Focused CBT and traditional CBT, and see how each approach impacts the healing journey.

A safe and secure childhood lays the foundation for healthy emotional and cognitive development — but trauma such as abuse, neglect, violence, or loss can disrupt that stability. Without proper support, these experiences can increase the risk of chronic illness, mental health challenges, and harmful coping behaviors later in life.

Both cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and its specialized form, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), help young people process trauma, manage distress, and rebuild a sense of safety — but they differ in focus and structure.

This guide explains how TF-CBT differs from traditional CBT, how each approach works, and how to choose the approach that best fits your child’s needs.

Key takeaways:

- Trauma can significantly affect a child’s development and increase the risk of later mental health and physical problems.

- CBT and TF-CBT are both evidence-based treatments for children and teens, but they differ in their approach and focus.

- The best fit depends on factors like trauma exposure, readiness, caregiver involvement, and access to qualified mental health providers.

TF-CBT vs CBT: Core differences

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) and CBT are both evidence-based talk therapies that demonstrate strong effectiveness, but serve different needs and populations.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy is a broad, goal-oriented therapy that can treat a wide variety of issues in people of all ages.

- Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy is a specialized adaptation of CBT, specifically designed for children and teens typically ages 3 to 18 who have experienced trauma and retain at least some memory of the event.

TF-CBT even works for children as young as 3 years old, using age-appropriate tools and techniques (such as play, drawing, stories, and parent participation). Standard CBT works for people of all ages.

CBT focuses on present-moment problems and how our perception of events, rather than the events themselves, influences behaviors and emotions. TF-CBT, by comparison, directly targets traumatic experiences. It also incorporates trauma-specific techniques (like creating a trauma narrative and guided exposure to trauma memories) that are not part of standard CBT.

Another key difference is caregiver involvement. TF-CBT actively involves non-offending parents or caregivers as therapeutic partners. Therapy sessions typically include conjoint parent-child sessions and parallel individual sessions, where caregivers receive coaching and learn parenting skills. Standard CBT is usually one-on-one, with caregiver participation as needed, but not built into every session.

The session structure also differs. CBT sessions are typically 50–60 minutes, weekly for about 8–12 weeks, and do not prescribe a child/parent split. TF-CBT is a short-term, structured protocol delivered in about 12–15 sessions for uncomplicated trauma and 16–25 for complex trauma.

Any licensed therapist can deliver CBT, and no special certification is required. TF-CBT requires specialized training and is supported by a certification pathway to ensure providers follow the model as intended.

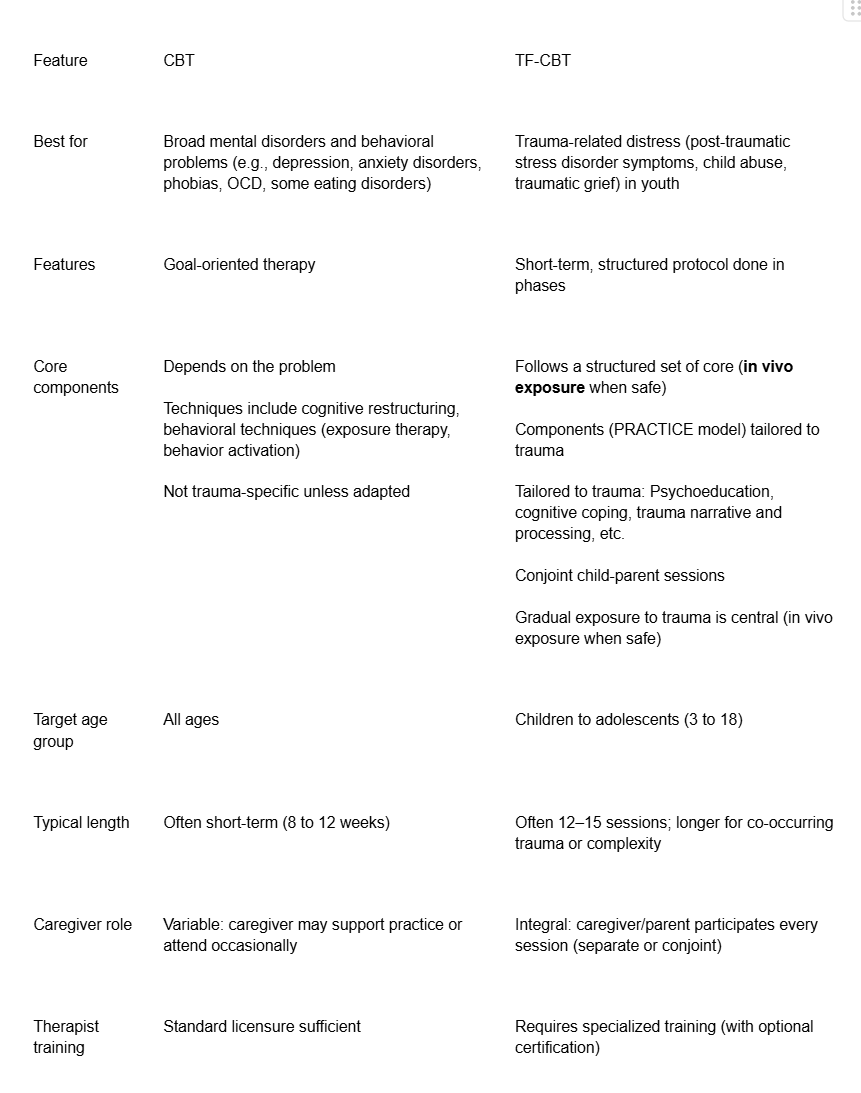

Key features table

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the key features of CBT and TF-CBT:

What is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)?

CBT is a structured, goal-oriented, time-limited approach used to treat a wide range of mental health concerns, including depression, anxiety disorders, OCD, phobias, eating disorders, substance misuse, and more.

CBT explores the link between thoughts, emotions, and behavior and rests on several fundamental principles:

- Psychological problems are influenced by negative thought patterns and unhelpful beliefs.

- Learned patterns of unhelpful behavior maintain these problems.

- People can learn better coping strategies that reduce symptoms and improve functioning.

CBT is fundamentally problem-focused and present-oriented, offering actionable solutions to immediate difficulties rather than deep exploration of the past.

This modality is not one-size-fits-all. It may not fully resolve severe or entrenched trauma-related issues on its own, and can be less effective for conditions like severe personality disorders or active psychosis.

What is trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT)?

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), a specialized form of CBT, is designed for children and adolescents who have been through traumatic events. It integrates CBT with attachment, humanistic, and family therapy principles. It is specifically designed to reduce post-traumatic stress, depression, and behavior problems, often in as few as 12 sessions.

Originally developed by Deblinger, Cohen, and Mannarino, TF-CBT was created to address post-traumatic stress disorder associated with sexual abuse (including sexually abused children), depressive symptoms, trauma-related symptoms, and emotional dysregulation.

It has since been adapted for:

- Physical abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Neglect

- Domestic violence

- Community violence

- Natural disasters

- War

- Traumatic loss

- Youth in foster care

- Military families

Its primary goal is to reduce PTSD symptoms and emotional/behavioral problems resulting from trauma. It also addresses the emotional reactions of non-offending parents and caregivers, those who weren’t involved in perpetrating the abuse. Caregiver sessions run in parallel to child sessions, recognizing that healing is stronger with consistent adult support.

The three phases of TF-CBT

TF-CBT is carefully structured into phases, each with specific goals:

Phase 1: Stabilization and skill building

Focus: Developing safety, trust, and skills to manage distress before addressing memories.

This phase builds a foundation of safety and coping tools. The therapist provides psychoeducation about trauma and typical reactions and teaches relaxation skills and emotional regulation to cope with distressing feelings that may arise. Parents learn parenting skills to reinforce stability and connection at home.

Phase 2: Trauma narrative and processing

Focus: Gradually telling and processing the child’s trauma at their own pace.

The child begins creating a trauma narrative: a spoken, written, or art-based story of what happened, while learning to challenge negative thoughts like guilt or shame through cognitive processing.

With the therapist’s support, repeated and safe exposure helps the memory lose intensity. In vivo exposure further helps children face real-life trauma reminders they’ve been avoiding.

Phase 3: Integration and consolidation

Focus: Applying skills and preparing for the future.

This final stage strengthens learned skills and supports lasting recovery. When the child is ready, they may share their trauma narrative with their caregiver during a conjoint session in the presence of the therapist and work on improving family communication.

The therapist guides safety planning and sets treatment goals that promote confidence and long-term healing.

The PRACTICE components

The core components of TF-CBT can be remembered by the acronym PRACTICE, whose sequence guides delivery. Caregivers move through the components in parallel with their child:

- P – Psychoeducation and parenting skills

- R – Relaxation and stress management skills

- A – Affective expression and modulation

- C – Cognitive coping and processing

- T – Trauma narration

- I – In vivo mastery of trauma reminders

- C – Conjoint child-parent sessions

- E – Enhancing safety and future development (safety planning)

Effectiveness and outcomes

Both CBT and TF-CBT are evidence-based, effective therapies for children and teens, though their focus and target populations differ.

Decades of research support CBT as a first-line option for many youth conditions.. A systematic review found that teens who received CBT were 45% more likely to no longer meet criteria for depression and 36% more likely to recover compared with control groups. Another randomized controlled trial reported large reductions in anxiety after 10 weeks of therapist-supported online CBT, with half no longer meeting diagnostic criteria three months later.

The benefits of CBT can also last well beyond treatment. One review found a 63% lower risk of later depression among teens who completed CBT, and a Japanese study showed that preschoolers who joined a CBT-based early intervention were far less likely to develop anxiety five years later.

TF-CBT is one of the most rigorously researched trauma-focused therapies for youth and is considered the gold-standard childhood PTSD treatment. It outperforms several alternatives for trauma-specific outcomes. A meta-analysis showed strong gains in emotional regulation, functioning, and resilience among traumatized children, including those who experienced sexual abuse.

These outcomes are not just short-term; many children maintain progress a year or more after completing therapy. A systematic review of ten clinical trials found TF-CBT significantly reduced PTSD symptoms, depression, and anxiety, with improvements that lasted long after treatment ended. Caregivers also benefit from improved parenting confidence and connection with their child.

Pros and cons: When to choose TF-CBT or CBT

Both therapies have their advantages and challenges, and understanding these can help you decide which might be a better fit for your situation and needs.

Here are the key benefits of CBT:

- Highly versatile, addressing a wide range of conditions in settings like schools, clinics, community centers, and treatment centers

- Goal-oriented and collaborative, helping teens stay focused on progress

- Shorter-term than many other therapies, often showing results within weeks

- Flexible delivery formats, including individual, group, digital, or online therapy

- Easier emotional entry point for those not ready to revisit traumatic memories

However, it also has its limitations and potential challenges:

- Present-focused, so it may not fully address deep-rooted trauma or family dynamics

- Requires active participation; progress depends on engagement and practice between sessions

- May be less effective for severe or complex trauma without added support

- Can feel too structured for those seeking a more exploratory style

Meanwhile, here’s where TF-CBT stands out:

- Effective trauma treatment for children and teens with post-traumatic stress or trauma-related distress

- Structured and short-term, following clear, phased goals

- Caregiver participation strengthens the parent-child relationship and supports recovery at home.

- Builds coping skills and emotional regulation before confronting traumatic memories to promote resilience

- Addresses both trauma symptoms and overall functioning

It also comes with potential challenges and limitations:

- Requires consistent caregiver involvement and steady attendance.

- The trauma narrative and gradual exposure components can feel emotionally intense (although temporary distress is normal)

- Not suitable when there’s ongoing danger, active substance use, or severe conduct problems

- Access may be limited to therapists with specialized training or certification

- Requires commitment and readiness from both the child and the caregiver to achieve the best outcomes

How to choose the right therapy for your teen

Every teen is different, and finding the right fit should be thoughtful and collaborative. Consider:

- Trauma exposure: If trauma is central, TF-CBT is often the first choice; without a clear trauma history, CBT may be more appropriate.

- Readiness and comfort: If your teen is hesitant to discuss memories, starting with CBT can build skills and trust before trauma-focused work.

- Caregiver involvement: TF-CBT expects active caregiver participation (but can still work for children who don’t have a parent available. If that’s not feasible, consider CBT or individual therapy first.

- Complex needs: With multiple concerns (depression, anxiety, substance use), therapy may need to be tailored, combined, or sequenced with other forms of mental health treatment

- Developmental readiness: Children need verbal skills roughly equivalent to a two-and-a-half-year-old to participate in trauma processing.

- Safety and stability: Begin TF-CBT only once your teen is safe and no longer exposed to ongoing trauma.

- Practical factors: Consider cost, insurance coverage, scheduling, and availability. Online therapy can expand access when local options are limited.

A licensed therapist who works with youth can help recommend the best path. At Emora Health, a brief online intake matches families with the right specialist for their child’s goals and needs.

Different types of child therapy

If you’d like a deeper look at the advantages and limitations of various child therapy approaches, you can read more in this article.

Finding a qualified TF-CBT therapist

Online therapy platforms like Emora Health can connect families with TF-CBT-trained providers. It’s best to look for clinicians experienced with your child’s inclusion criteria (age, trauma type, co-occurring conditions).

When choosing a therapist, consider asking these questions:

- How much TF-CBT experience do you have?

- Where did you train, and do you receive ongoing supervision or consultation?

- What does treatment typically look like (session count, caregiver involvement, progress tracking)?

- How do you measure progress and adjust if needed?

- Are you comfortable with the trauma my child experienced?

How Emora Health can help

Childhood trauma can leave lasting effects on a child. Choosing between CBT and TF-CBT largely depends on whether trauma is central to your child or teen’s challenges.

Emora Health can make your decision easier. Our team can connect you with licensed therapists experienced in trauma-focused care, including certified TF-CBT providers, matched to your child’s needs, location, and insurance coverage. We provide coordinated care in a supportive environment to promote steady progress and long-term healing.

If you’re ready to start, our brief online intake form can help match you with a trauma-informed therapist who can help your child heal and grow.